Providing Equitable Education as a Daily Call to Action

By Dr. Jeff Wagnitz and

Dr. Rolita Flores Ezeonu

This piece first appeared in ”Working Toward an Equitable and Prosperous Future for All: How Community Colleges and Immigrants Are Changing America,” edited by Jill Casner-Lotto with Teresita B. Wisell (Rowman & Littlefield, October 2019).

It’s Monday morning, early in fall quarter. Two dozen hijab-clad women crowd the narrow entryway of Building 19, located at the heart of Highline College’s main campus. Past the entry, across the reception area inside, a student-painted mural fills the wall on the other end of the space, some 20 feet into the building. The image portrays the faces of four women, representing different points on the globe. One is wearing a hijab.

A painted mural depicting four women greets visitors and students, many of whom are immigrants and refugees, in the entryway of Highline College’s Building 19.

The mural’s visual message of including, embracing and encouraging campus diversity is what we strive for in our services and programmatic offerings. Equity is our goal, and we believe that diversity is our greatest asset in getting there. Welcoming newcomers is step one.

Building 19 is home to Highline’s Adult Basic Education (ABE) department, which houses English as a second language (ESL) classes, Puget Sound Welcome Back Center (PSWBC) and several transition-to-college programs. As such, it is the college’s entry point for most immigrants and refugees like this group of Somali women. But Highline’s commitment to its global population is campus-wide and deeply woven into the institutional culture.

In this chapter, we trace that commitment, beginning with a look back into the college’s earliest years, when its values took shape. From there, we review several initiatives that represent Highline’s present-day response to the region’s immigrants and refugees from dozens of countries, 6,300 of whom enrolled at Highline in 2016–2017, accounting for more than one-third of our student population. [1] Finally, we identify lessons learned.

A Brief Look Back

When Highline College opened its doors in 1961 to 385 students, it became the first community college in King County, Washington. By fall of 1964, nearly 3,200 students were enrolled either part time or full time, and 1,000 qualified applicants had been refused admission due to limited space on the new campus, outpacing construction of new buildings. [2]

During those early years, the college’s students largely represented the growing middle-class families who lived in the suburban area, tucked in the southwestern corner of the county, some 20 miles south of Seattle. White faces fill the photos in the student newspaper and yearbooks of that time. Racially and ethnically, the faculty members in those early years resembled the students. The lack of diversity was such that when a person of color did join the faculty, it made headlines in the college’s student newspaper, the Thunder Word: “HCC Gets Black Instructor.” [3]

Junki Yoshida

Even in the college’s early years, Highline was a welcoming place for immigrants, despite their rarity. In fact, two of Highline’s most notable early alumni are immigrants, Junki Yoshida from Japan and Ezra Teshome from Ethiopia. Both attended Highline in the early 1970s and went on to become successful businesspeople, philanthropists and humanitarians. [4]

Ezra Teshome

Over the years, little by little, more and more immigrants and refugees made their way to the college, fleeing wars and conflicts around the globe, economic hardship and more. A 1980 Thunderword article reported on 170 refugees from China, Laos and Vietnam who had found a new life here. [5]

Then came the 1990s. In that decade, diversity on campus began its upward climb in earnest. The reasons are many.

For one, housing in the area was relatively inexpensive, making it a draw for the region’s newer residents, many of them immigrants and young families. Further, the suburban area’s airport-, hospitality- and retail-dependent economy offered ready opportunity for entry-level employment. About that same time, the International Rescue Committee set up an office in Seattle and began settling refugees in Tukwila, a small city in our service area. The area welcomed Bosnians and Serbs. More Laotians and Vietnamese came, too. Next came Eritreans, Ethiopians and Somalis. More recently, Afghans, Burmese, Iranians and Iraqis have arrived. [6]

Today, Tukwila’s residents number 20,000, 41% of whom are foreign-born. [7]

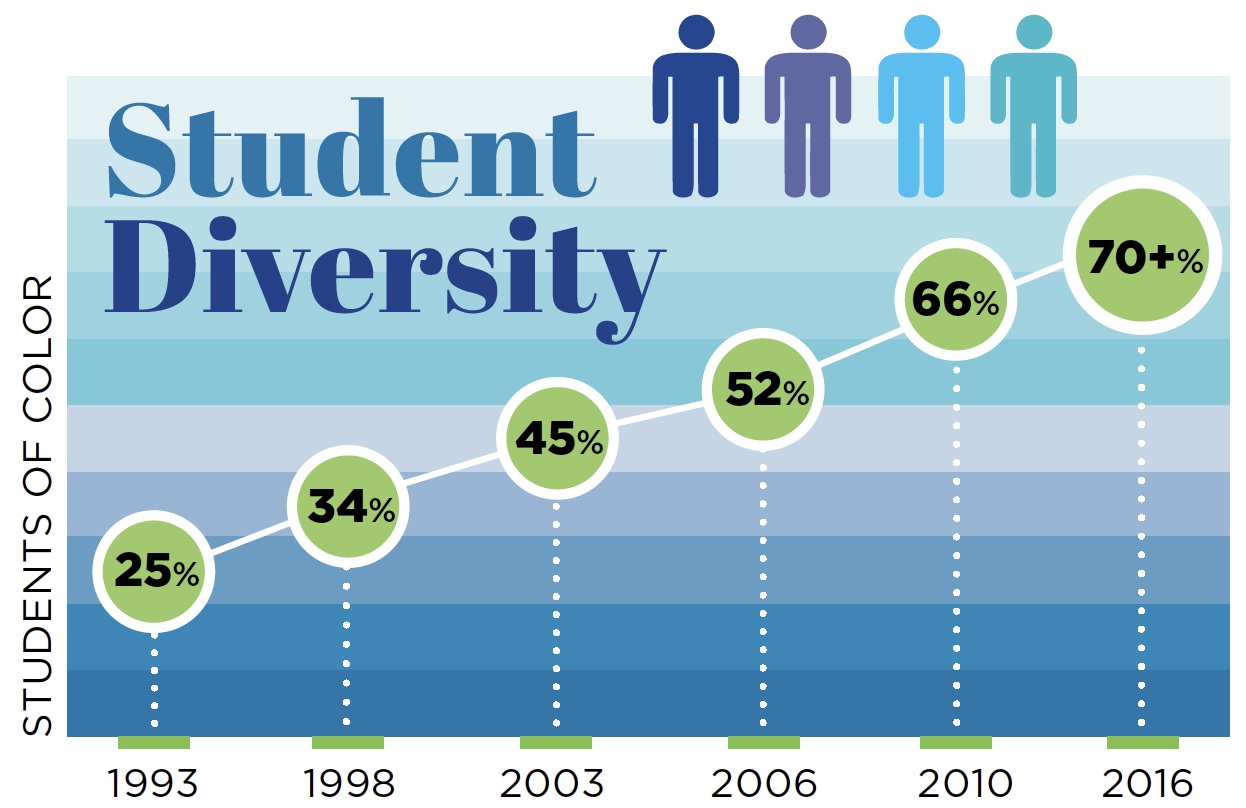

As the diversity of the area’s population increased, so did the diversity of Highline’s student body, rising from 25% students of color in 1993 to 34% five years later. By then, 17% of our students also identified as immigrants or refugees. The trend continued into the next decade. In 2003, the college had 45% students of color. By 2006, the number had risen to 52%, and in 2010, to 66%. [8]

As the diversity of the area’s population increased, so did the diversity of Highline’s student body, rising from 25% students of color in 1993 to 34% five years later. By then, 17% of our students also identified as immigrants or refugees. The trend continued into the next decade. In 2003, the college had 45% students of color. By 2006, the number had risen to 52%, and in 2010, to 66%. [8]

Now, more than five decades after its founding, Highline is the most diverse higher education institution in the state, with more than 70% students of color and people representing more than 120 cultures and ethnicities. Today, Highline’s 17,000 students are a microcosm of the world. [9]

Founding Faculty, Foundational Values

For many institutions, this dramatic change in demographics could be viewed as a challenge. But for Highline, a critical cultural dynamic was at work, profoundly shaping the trajectory of the institution.

Faculty who had been the backbone of the college from its earliest years had created the expectation that our college was, at its heart, a social justice institution. The initial champions were a comparatively diverse group of men who found each other on campus and clicked through their common interest. They had come from California and the central area of Seattle, where social justice issues were at the forefront.

As new faculty came on board, these early faculty leaders spread the word, sharing with others on campus their belief in justice for all, this idea of the college as a social justice institution. There were doubters and detractors, of course, but the dominant voices were strong and committed to the social justice cause. These forward-thinking faculty — who could not have anticipated the demographic and socioeconomic changes to come in the region — were critical as our institution responded.

Committing Values to a Tangible Plan

Although indispensable, values alone can’t drive institutional change. For Highline, the transition from aspiration to tangible planning came in 1994 when, to satisfy an accreditation recommendation, the college launched a strategic planning process that included students, faculty, staff, administrators and community members. The process sought to review the institution’s strengths, weaknesses and role in the community. The three resulting strategic initiatives revealed the college’s initial effort to commit its values into a college-wide manifesto:

- Initiative 1: Create a college climate that attracts, welcomes, enrolls and retains students.

- Initiative 2: Expand visibility and involvement of the college with the community.

- Initiative 3: Create a college climate that values diversity and enhances global perspectives. [10]

Our mission and strategic plan guided us as Highline’s diversity continued its rise. As Highline’s planning became more sophisticated and data driven, its strategic goals were eventually quantified in a Mission Fulfillment Report that, to this day, monitors the college’s success in supporting its immigrant and refugee communities. To meet those objectives, the institution has implemented a variety of interventions and has sustained a variety of commitments. The examples that follow illustrate some of these initiatives and promises.

Programmatic Responses

English as a Second Language

Nearly 80% of our immigrant and refugee full-time equivalent (FTE) student population is enrolled in our ESL program, constituting the largest cohort of any community college in Washington. [11]

Because tuition is waived for these noncredit courses, the college forgoes more than $2 million annually in revenue. Granted, an element of pragmatism is at work here, given that without this population of students, we would sometimes be hard pressed to meet enrollment targets. But our college leadership does not use enrollment targets as a rallying cry to motivate faculty and staff to embrace the work involved in serving our ever-increasing newcomer community. Rather, the college’s culture, the commitment to social justice that drives our work daily, provides the motivation. It is an intentional choice on our part.

For some students, simply improving English skills is their goal. However, we encourage them to progress to college-level courses. To meet those goals, we have piloted, refined and institutionalized a number of programs and interventions. Some examples follow.

I-BEST

Highline College was among the first community colleges in the state to offer Integrated Basic Education and Skills Training (I-BEST). [12] The intent of I-BEST is to eliminate years of remediation work and, instead, pair basic academic skills and language courses with college-level occupational skills courses in in-demand career fields. Two or more instructors teach the courses, ensuring students are supported. Currently, Highline offers certificates in four areas: business technology, education, hospitality and tourism, and health care. Students choose from close to a dozen certificates, including customer service, early childhood education, hotel operations and home care aide.

We have found I-BEST significantly accelerates student attainment of college-level credits and increases student retention. Students learning English are often frustrated by the time it takes to progress from one level to another in ESL courses. Pairing such courses with relevant content, leading to an I-BEST certificate — and employment possibilities — provides a significant motivator for student retention.

Those students in intermediate ESL, known at Highline as Level 4, can usually complete a certificate within three to 12 months. Along the way, they learn job training and college readiness, both important areas to support immigrants who are unfamiliar with college and careers in the United States. Once students complete an initial certificate, they can find employment in their chosen career, which, in turn, will help them increase their language skills on the job. Students can return to Highline to pursue additional certificates. As they add certificates — and thus credits — they gain momentum on their way to an associate degree.

Jumpstart: A Transition-Support Program for ESL Learners

Another transition-support option is Jumpstart, a homegrown program started in 2010. [13] The idea came about during a brainstorming session of our ESL-to-Credit Task Force, formed as part of our Achieving the Dream (ATD) initiative. The ATD initiative leads a national network of community colleges committed to closing achievement gaps; increasing attainment of degrees and credentials; and improving economic opportunities for their students, particularly low-income and students of color. [14] The Highline group was trying to identify unique and innovative solutions to help our higher-level ESL students transition to college-level courses. Students apply for Jumpstart and, if accepted, receive a “scholarship,” which is actually a tuition waiver.

Participants take the highest level of mainstream pre-college reading and English classes, along with a supplemental support class, all tuition-free. Students who meet the outcomes of the English and reading classes are able to continue to English 101 and other college-level classes. The supplemental support class ensures that students are successful by providing a review of English and reading concepts, help with college navigation, and intensive academic advising.

There is a cost to the college, in that English and reading faculty are teaching a class that could have gone to tuition-paying students. But the program’s outcomes are worth it. Data as of winter quarter 2018 show that 248 students participated in the 25 Jumpstart cohorts between winter 2010 and spring 2016. Of those students, 204 (82%) went on to take at least one college course; 174 (70%) took at least 15 credits; and 71 students (29%) have completed their program of study (which includes two-year degree and certificate programs). [15] There are qualitative successes, too. Faculty report students “come alive” in Jumpstart, writing more and better than they thought possible and bonding as a cohort. [16]

Off-Site Classes

Research, as well as anecdotal evidence, indicates that commute times to classes can be a significant barrier for students in deciding whether to pursue an education. That effect is magnified among basic skills learners.

According to a Washington State Board for Community and Technical Colleges study, approximately 40% of students in Highline College’s catchment or service area travel 10 minutes or less to attend college-level classes. For ESL students, by comparison, the figure is nearly 70%. For those traveling between 10 and 20 minutes, another disparity becomes evident: close to 50% of students in college-level classes make that commute compared to just under 30% of students in ESL classes. [17]

The data show us that ESL students are more likely to travel only a short distance to attend classes, compared with all students in college-level classes. For the immigrants and refugees in our community, who juggle families, jobs and more, even a relatively short 10- to 20-minute commute to campus can be a deterrent. Given that immigrant communities are distributed widely across Highline’s district — and that the results were similar for other metro-area colleges across the state — it is reasonable to infer that longer commute times inherently inhibit participation.

Our response has been to offer classes in strategic locations in a number of communities where students live and work. One such location is at a YWCA in White Center, a community 10 miles north of our main campus. At this particular location, all students are refugees and immigrants. Approximately 150 students attend each quarter, most of whom are English-language learners. [18] At that site, our Education department offers early childhood education classes in several language cohorts, including Arabic, Somali and Spanish. Many of the students are early childcare providers working toward their state credentials. For those students, we offer three stackable early childhood education certificates.

Our Continuing Education department also offers a variety of classes, such as home care aide, health care interpreter and customer service.

Puget Sound Welcome Back Center

One of 10 centers across the nation, PSWBC helps internationally educated professionals recertify to work in the United States. [19] Like many of Highline’s services to local immigrant populations, PSWBC grew from the passion and good ideas of faculty and staff here.

During the 2006–2007 academic year, an English teacher in our immigrant and refugee ESL program heard again and again that her students were doctors, nurses and pharmacists in their countries, but were working as taxi drivers, fast food workers and warehouse employees in the United States. She explored options of recertification for internationally educated health care professionals and discovered the national Welcome Back Initiative (WBI), which started in San Francisco, California, in 2001 and helps foreign-trained health care professionals enter related careers in the United States.

WBI’s national network consists of 10 Welcome Back Centers in nine states. Five are based in community colleges, and others partner closely with community colleges or other community or adult education organizations. [20] After flying to San Francisco to learn more, the English teacher presented the idea to college administrators, who approved of starting a center at Highline. She then brought together college faculty and staff as well as community partners from a variety of organizations to make it a regional effort and help with funding.

Since PSWBC opened its doors in 2008, it has served more than 1,200 health care professionals, including 726 nurses. In 2014, the center began helping professionals in other fields: 230 in STEM and business fields and 140 from a variety of other occupations, including 52 teachers. All told, close to 1,600 participants have been helped at the center. [21]

Highline’s approach and institutional support for the center differs from many, if not all, of the other centers. Those who seek assistance from PSWBC are called “participants,” not “students,” since those who qualify for services will often not enroll in a Highline class. They may take other courses designed to prepare for licensure exams, such as the National Council Licensure Examination (NCLEX) for nurses, but more often than not, they never become a Highline student. Instead, the center partners with outside organizations to provide services.

To help its internationally educated nurses prepare for licensure in the United States, for example, PSWBC partners with Kaplan, a test preparation company, to offer classes to prepare for NCLEX. PSWBC publicizes the course and offers free orientations during the summer. Kaplan charges $500 for the course, which includes four months of online learning and three months of face-to-face instruction from Kaplan. For those unable to pay, PSWBC looks for funding sources to offset some or all of the course and textbook costs. [22]

Having PSWBC participants enroll in classes outside of Highline’s offerings was not the original intent when we envisioned the center, but it has become the prevailing practice, based on the needs of our area’s immigrants and refugees. Our belief in the benefits of the center outweighs the financial downside. It speaks to our overall commitment to serving this population of our community and contributes to workforce development.

Transition Center and Working Students Success Network

In October 2008, Highline created the Transition Center to provide in-depth academic advising, financial assistance, outreach and workshops, all designed to help our ABE/ESL students understand their educational and career options, develop plans, secure funding and navigate the college. The Transition Center came about as the result of qualitative studies, surveys and, again, the ideas of our employees.

Focus groups revealed that 80% of upper-level ESL students were interested in pursuing degrees or certificates, but knew little or nothing about what the college could offer, what it might cost, how to pay for it, or how to get started. The college’s processes and programs, so familiar to the experienced local consumer, were seen as impenetrable to first-time students from faraway countries with different education systems. [23]

Offering further evidence, data from the Community College Survey of Student Engagement (CCSSE) revealed that, among immigrant students who had transitioned successfully to credit curriculum, the reliance on college support resources was high. This suggested to us that an important component of the college’s strategy would be to engage these students early on with services such as advising, tutoring and financial aid. CCSSE is administered by the Center for Community College Student Engagement to Highline students approximately every three years, providing valuable feedback to ensure institutional effectiveness. [24]

Through conversations, participants emphasized the importance of relationships with faculty, staff and fellow students. A friendly, accessible and knowledgeable contact person could play a significant role, students said, in helping them navigate processes and meet key people on campus. [25]

Today, the Transition Center plays an important role in the development and advancement of immigrant and refugee students by connecting these students with academic programs and leadership opportunities not only to advance themselves, but also further promote the college’s mission of globalism and diversity.

The college’s social justice orientation also requires that we confront income inequality, which disproportionately affects communities of color and English-language-learner communities. To integrate our response to these intersections of circumstance, the college chose to co-locate its Transition Center — as well as other support services such as Workforce Education Services (WES) — as part of the Working Student Success Network (WSSN) facility, established at Highline as part of our Achieving the Dream (ATD) initiative. These support services [26] are together in Building 1, located a short distance from Building 19, mentioned earlier as the entry point for most immigrants and refugees. Building 1 has recently been remodeled so that those support services are integrated with initial assessment and placement, pathway selection and faculty advisor assignment.

Funding for support services comes from a variety of sources. Students participating in WES, for example, receive tuition and other financial assistance from the state’s Employment Security Department. WSSN was initially funded as a grant, now incorporated into our base budget.

The Transition Center and WSSN actively work toward supporting the central themes to ATD, of which Highline College is currently a leader school. WSSN focuses on three areas: (1) education and employment advancement; (2) income and work supports, which include financial aid advising; and (3) financial services and asset building, such as financial education and coaching. The Transition Center directly supports the first two areas by advising students on transitioning from noncredit to credit-bearing classes, connecting students with employment and career resources, and helping students navigate financial aid options. With this synergy, students are surrounded by Highline professionals ready to support their transition, retention and completion.

Lessons Learned

Lesson 1: Build on Campus Values

The strongest arguments for institutional change develop when philosophy and pragmatism meet. We were fortunate to have that synergy during the 1990s when we undertook a comprehensive strategic planning process. Our rapidly diversifying community needed a college that could respond to its unique needs. And our college had two generations of faculty who were deeply committed to social justice. The campus was primed to accept and embrace the work. Without that synergy, any executive-level push for change would surely have fallen flat.

Over the past two decades, subsequent revisions to our mission statement and the strategic plan reflect our ongoing commitment to increase diversity and educational and social justice equity. The culture of support for our diverse community has been woven into the fabric of the college. We view providing an equitable education as a core value, a source of pride and a daily call to action.

In fact, our college has been recognized nationally for its commitment to increasing diversity, equity, inclusion and social justice. Highline is a four-time winner of the Higher Education Excellence in Diversity Award, the 2016 winner of the Association of Community College Trustees Equity Award for the Pacific Region, and the 2014 winner of the American Association of Community Colleges’ Award of Excellence for Advancing Diversity.

Lesson 2: Create and Measure Mission-Level Commitment

The mission-level leadership environment of today that supports immigrant and refugee education owes its origins to the 1990s strategic planning process and the campus culture that nurtured it. Our strategic plan gives us a tangible tool to guide us. We then measure our progress in fulfilling the plan’s initiatives using data. Those data are instrumental in finding weak spots in student attainment and prompting faculty and staff to take a hard look at curriculum and come up with new programs and interventions.

We believe in the axiom “what gets measured gets done.” Anyone reading our Mission Fulfillment Report, and the data therein, should be able to tell what we value as a college.

Obtaining the necessary data became a priority in the 2000s.

In 2006, the MetLife Foundation named Highline as a finalist in its Community College Excellence Awards, demonstrating our campus-wide commitment to serving the traditionally underserved. At that time, based on our institution-wide work during the strategic planning process of the 1990s and a comprehensive development plan created in 1998–1999, we were able to demonstrate to the MetLife Foundation that Highline had achieved substantial gains creating successful pre-college and college experiences for traditionally underserved students.

But we knew then that our accomplishments were not enough to meet the needs of ABE/ESL students, an area of steady growth. As a next step, we applied for, and were accepted into, the national ATD initiative, welcoming the opportunity to further develop our culture of evidence, whereby student performance and attainment data informed our decision-making processes. Through participating in ATD, we looked to strengthen our work in four areas: [27]

- Expand and refine community-to-campus initiatives.

- Strengthen academic support services.

- Strengthen and integrate developmental education.

- Improve advising and student information services.

All four areas speak to our desire to help immigrants find success in college, with ESL transitions, specifically, a major focus.

As part of ATD’s initial data-analysis protocol, we found that, as Highline’s ABE/ESL enrollments grew, immigrant students were persisting into college-level coursework at a low rate. For example, the fall-to-spring transition rate (academic year 2004–2005) from ABE/ESL into college credit was less than 1% — a disappointing figure, but in line with national trends. Buoyed by our inclusion in ATD, we began investigating the progression shortfall of our ABE/ESL students. [28] To provide encouragement and accountability, we set a stretch goal of improving the rate to 10%.

Today, immigrant and refugee students’ transition rates have improved. Data from 2016–2017 indicate that 4.7% of immigrants (N = 936) and 7.6% of refugees (N = 251) transitioned from noncredit to college-level courses. [29] We have work to do to meet our 10% goal, but the figures represent significant gains from the mid-2000s.

Data from 2016–2017 also indicate that immigrant and refugee students are completing their courses of study. In that year, these students earned 149 associate degrees, 140 certificates (ranging from short-term certificates under 20 credits to longer certificates over 45 credits), and five applied bachelor’s degrees, which are relatively new on our campus. [30] We are confident that the increase in recent transition rates will result in an increase in completion rates in the next few years.

Lesson 3: Incorporate Pragmatism

We talked about wedding philosophy and pragmatism in Lesson 1. Here we speak more specifically about our pragmatic reasons. In addition to meeting our college’s enrollment targets, mentioned earlier, three reasons come to mind, all which speak to fulfilling our mission as a comprehensive community college:

- To meet Washington state’s evolving economic and workforce needs, at least 70% of the state’s adults, ages 25–44, will have a postsecondary credential by 2023. [31]

- To reduce the brain waste that occurs when a highly skilled individual is either unemployed or underemployed because their skills, qualifications or education is not recognized.

- To reduce the need for social services that drain resources when immigrants and refugees are unemployed and underemployed.

Lesson 4: Encourage Trust and Innovation

Our collective belief in social justice paved the way to embrace the demographic changes within our student population. What was also crucially important — especially to making curricular and programmatic changes — was, and remains to this day, the college’s culture of collegiality, built on strong relationships, mutual respect and cooperation.

It is a “high-trust environment,” in the words of our faculty union president. [32] It is also a high-dedication environment. On our best days, those qualities reinforce one another, fostering innovation, high expectations and joyful hard work within a climate of mutual confidence, interdependence and support. We want each other to succeed, not for our own sake, but for advancement of our community, our students and our values.

In 2003, an accreditation team even made note of our culture, giving the college a commendation for our “special spirit.” The team’s report commended us for our collegiality, for the respect and appreciation we demonstrate to each other, and for the way we consistently demonstrate the college’s values in our work and our programs. [33] Collegiality and trust nurture an entrepreneurial spirit among staff and faculty, leading to innovative programs and services designed to meet the challenges of serving our immigrant and refugee communities. The Jumpstart program is a prime example. It was developed in a safe environment for risk-taking and entrepreneurship and supported by a trusting administration.

Lesson 5: Focus on Assets

We look to fulfill the hopes and dreams of those who seek us out. Although hope is a rather nebulous concept, we find a tangible expression of it in our asset-based philosophy of working with students. We work hard to emphasize what students do know when they begin at Highline and build on those assets, rather than the deficit perspective of focusing on what they lack.

Perhaps the clearest example of this approach is through PSWBC mentioned earlier. PSWBC recognizes and works with the professional credentials and educational and work experience of newcomers. It then builds on those assets to equip newcomers for their next step toward their career, rather than having them start the educational process from the beginning.

One Student’s Success Story

We began our story with the Somali immigrants in Building 19, who were likely at the beginning of their educational journey at Highline. We will close with a look at one immigrant and how a few of our programs helped him achieve a significant milestone in his education.

Born and raised in Lima, Peru, Emilio originally came to Highline in 2013 to brush up on his English skills for an entry-level job. His ESL Level 3 instructor persuaded him to take an ESL transition class, enabling him to explore careers and find support for moving to college-level classes. At that point, he was still undecided. Again, with her prompting, he applied for Jumpstart and was accepted for winter 2014.

Emilio had his share of struggles, so much so that he often wondered which one was the worst. With every obstacle he overcame — learning English, developing keyboarding skills so he could complete assignments on time, and creating effective study habits, to name just three — he gained more and more confidence, creating a positive feedback loop.

He made the most out of his college experience, getting involved in our Center for Leadership and Service and the Inter-Cultural Center, where he made friends and built skills and confidence. He sought help in our Writing Center and from his instructors when he doubted his abilities. And, he took a part-time job as a reading/ESL/study skills tutor in our Tutoring Center. There, he discovered his love of teaching.

By spring of 2018, Emilio had earned an associate degree and proudly crossed the stage during our commencement ceremony, with plans to remain at Highline to pursue an applied bachelor’s degree in early learning and teaching, with the goal of becoming a teacher. [34]

For immigrants like Emilio, the journey from Building 19 to the commencement stage is not without its challenges. It is incumbent upon us as an institution to continue to refine our processes and programs in an effort to improve the educational journey for these newcomers. After all, we all benefit from the assets they bring to our communities and to campus as we prepare students to live and work in a multicultural world and global economy.

About the Authors

Jeff Wagnitz, Ed.D., retired in 2019 after 18 years at Highline College, Washington’s most diverse higher education institution. He served as Highline’s interim president from 2016 to 2018 and, for the prior eight years, as vice president for academic affairs.

Jeff Wagnitz, Ed.D., retired in 2019 after 18 years at Highline College, Washington’s most diverse higher education institution. He served as Highline’s interim president from 2016 to 2018 and, for the prior eight years, as vice president for academic affairs.

Wagnitz began his 37-year career in community colleges teaching pre-college and college-level English. He holds a doctorate in educational leadership from the University of Washington Tacoma. In 2016, he earned the Award of Excellence in Leadership from Washington’s Community and Technical College Leadership Development Association.

Rolita Flores Ezeonu, Ed.D., has more than 20 years of experience in higher education, both in the classroom as a tenured faculty member and in administrative leadership. She has implemented and coordinated targeted initiatives and programs to strengthen student retention, transitions and completion for students of color and immigrant and refugee populations. She was appointed vice president for instruction at Green River College in July 2018.

Rolita Flores Ezeonu, Ed.D., has more than 20 years of experience in higher education, both in the classroom as a tenured faculty member and in administrative leadership. She has implemented and coordinated targeted initiatives and programs to strengthen student retention, transitions and completion for students of color and immigrant and refugee populations. She was appointed vice president for instruction at Green River College in July 2018.

Ezeonu served as Highline College’s interim vice president for academic affairs from 2017 to 2018 and as dean of instruction for transfer and precollege education from 2008 to 2017. She earned her doctorate in educational leadership with an emphasis in the community college from Seattle University and holds a certificate in “closing the achievement gap” from Harvard University Graduate School of Education.

Notes

The name of Highline’s student-run newspaper has evolved over the years from Thunder Word to Thunder-Word to Thunderword. The names used in this piece reflect the name at the time the article was written. Back issues, including all those cited in these notes, are available at the Thunderword Archive.

Likewise, Highline’s name has evolved. The college began as Highline College at its founding in 1961, changed to Highline Community College in 1967 and reverted to Highline College in 2014. The names used here reflect the name at the time.

1. Highline College Institutional Research Office. Data retrieved May 2, 2018.

2. Tim McMannon, “Our Award-Winning Campus (Buildings!): Construction in the 1960s and ’70s,” Highline College, 2012.

3. “HCC Gets Black Instructor,” Thunder Word (February 14, 1969): 8.

4. “Alumni Recognition,” Highline College, accessed May 1, 2018.

5. “Health Services Helping Refugees,” Thunderword (May 9, 1980): 2.

6. Ben Stocking, “The Revival of Foster High: School Filled with Refugees Makes a Comeback,” The Seattle Times (January 2, 2016).

7. “Quick Facts: Tukwila city, Washington, United States,” U.S. Census Bureau, accessed June 19, 2018.

8. “Title III Application, Comprehensive Development Plan,” Highline Community College, 1999.

9. Highline College Institutional Research Office. Student Profile, Academic Year 2017–2018.

10. “Title III Application, Comprehensive Development Plan,” Highline Community College, 1999.

11. Highline College Institutional Research Office and Washington State Board for Community and Technical Colleges Enrollment Reports. Data retrieved May 2, 2018.

12. “2012 I-BEST Review: Lessons Being Learned from Traditional Programs and New Innovations Next Steps and Issues for Scaling Up,” Washington State Board for Community and Technical Colleges (Research Report 12-01, June 2012).

13.“Comprehensive Self-Evaluation Report,” Highline Community College, August 2013.

14. “About Us,” Achieving the Dream, accessed August 12, 2018.

15. Jumpstart program. Data retrieved April 30, 2018.

16. Jumpstart program faculty, email message to author, April 12, 2018.

17. Eric Jessup and Jeremy Sage, “Washington State Community & Technical Colleges Transportation Access Study,” Washington State University School of Economic Sciences, 2009.

18. Workforce Education Services staff, email message to author, April 29, 2018.

19. “Puget Sound Welcome Back Center,” Highline College, accessed August 12, 2018.

20. “A National Network,” Welcome Back Initiative, accessed August 12, 2018.

21. Puget Sound Welcome Back Center. Data retrieved April 26, 2018.

22. “Feasibility Study: Welcome Back Center,” Highline College, 2016.

23. “2009 MetLife Short Application,” Highline Community College, 2009.

24. “About the Center,” Center for Community College Student Engagement, accessed August 12, 2018.

25. “2009 MetLife Short Application,” Highline Community College, 2009.

26. “Highline Support Center,” Highline College, accessed August 12, 2018,

27. “2006–2007 Achieving the Dream: Community Colleges Count Application,” Highline Community College, 2006.

28. “2009 MetLife Short Application,” Highline Community College, 2009.

29. Highline College Institutional Research Office. Data retrieved May 2, 2018.

30. Highline College Institutional Research Office. Data retrieved May 2, 2018.

31. “The Roadmap: A Plan to Increase Educational Attainment in Washington,” Washington Student Achievement Council, 2013.

32. Dr. James Peyton, meeting of the Highline College Board of Trustees, December 14, 2017.

33. Dr. Priscilla J. Bell, email message to college faculty and staff, April 30, 2003.

34. Emilio [pseud.], email message to author, May 1, 2018.