Our Award-Winning Campus (Buildings!): Construction in the 1960s and ’70s

By Dr. Tim McMannon

“Our Award-Winning Campus (Buildings!): Construction in the 1960s and ’70s” is the final in a series of vignettes by Highline history instructor Tim McMannon. Originally written in 2012 for Highline’s 50th anniversary, the piece has been reformatted for Highline’s website, giving more people a chance to learn about the college’s rich history.

Read McMannon’s other vignettes, “Highline College: Why Here? Why Then?” and “1968: Protest Comes to Highline,” both published electronically in conjunction with the college’s 55th anniversary celebration during the 2016–17 academic year.

Those of us who spend much time on Highline College’s campus know that it is a beautiful place. A wide variety of trees, well-kept flower beds and the sloping terrain make for visual interest. And the views of Puget Sound, Vashon Island, and the mountains of the Olympic Peninsula can be simply breathtaking.

Our perception of the campus’s beauty rarely extends to its buildings, however, especially the older ones, many of which look today look like so many little concrete boxes. But when they were constructed, Highline’s buildings were on the cutting edge of modern design, and they won recognition from both educational and architectural organizations. Yes, our campus buildings are multiple award winners.

Construction (and in some cases destruction) of campus buildings has been ongoing. There always seems to be some new project or renovation in progress. Most of the campus physical plant, however, was built in three phases: two in the 1960s and one in the 1970s.

Phase I: 1963-65

For its first three years — 1961–62, 1962–63 and 1963–64 — the college was housed on a temporary basis at Glacier High School. At Glacier, college classes and activities were carried out in portable buildings and, in afternoons and evenings, high school structures that were not in use for secondary school functions. The situation was tolerable but hardly ideal, and efforts to build a separate campus were initiated as soon as the Highline School District got permission to found the college in 1961. [1]

School leaders, advisory committee members, and architect admire campus mockup. From left: Highline College President Melvin “Pat” Allan, Reynold Stone, Highline College Dean of Instruction Charles Carpenter, Architect Ralph Burkhard, Mrs. Harold Mansfield, Highline School District Superintendent Carl Jensen, Highline College Director of Curriculum Shirley Gordon, Arnold Tjomsland, Peter Armentrout, Mrs. Georgia Keefer and Foster Kirk.

By August 12, 1963, when groundbreaking ceremonies were held for the new campus, three major milestones had been achieved. First, a suitable 80-acre site had been secured just west of Pacific Highway South at South 240th Street in Midway. The land was held by the state as part of the education land grant provided by the federal government, so a favorable 20-year lease was arranged. [2]

Second, about $2.4 million in construction funding had been arranged in the forms of a Highline School District bond ($711,000) and matching state grants ($1.7 million). The first bond vote had failed, but through effective lobbying, college supporters secured an overwhelming 87 percent approval on the second try. [3] The state grant had likewise faced a hurdle — a court case challenging the state’s authority to sell school bonds — but a favorable decision by the state Supreme Court had cleared the way for the grant money to flow and the campus to be built. [4]

Third, architect Ralph H. Burkhard had produced a campus design approved by both the Highline School Board and the state Board of Education. Burkhard was known for innovative, modern, award-winning designs, and he had extensive experience in school architecture. [5]

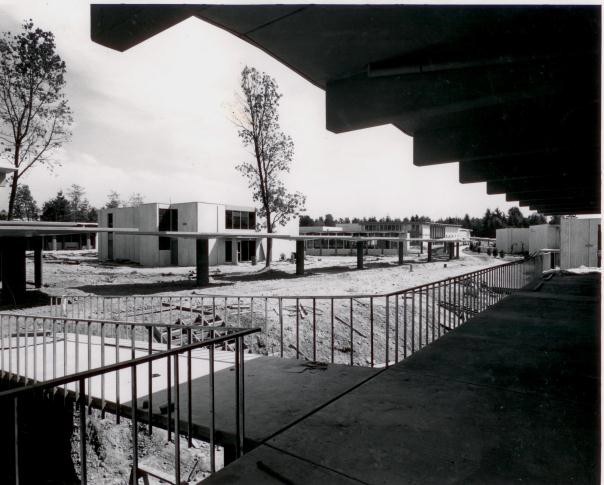

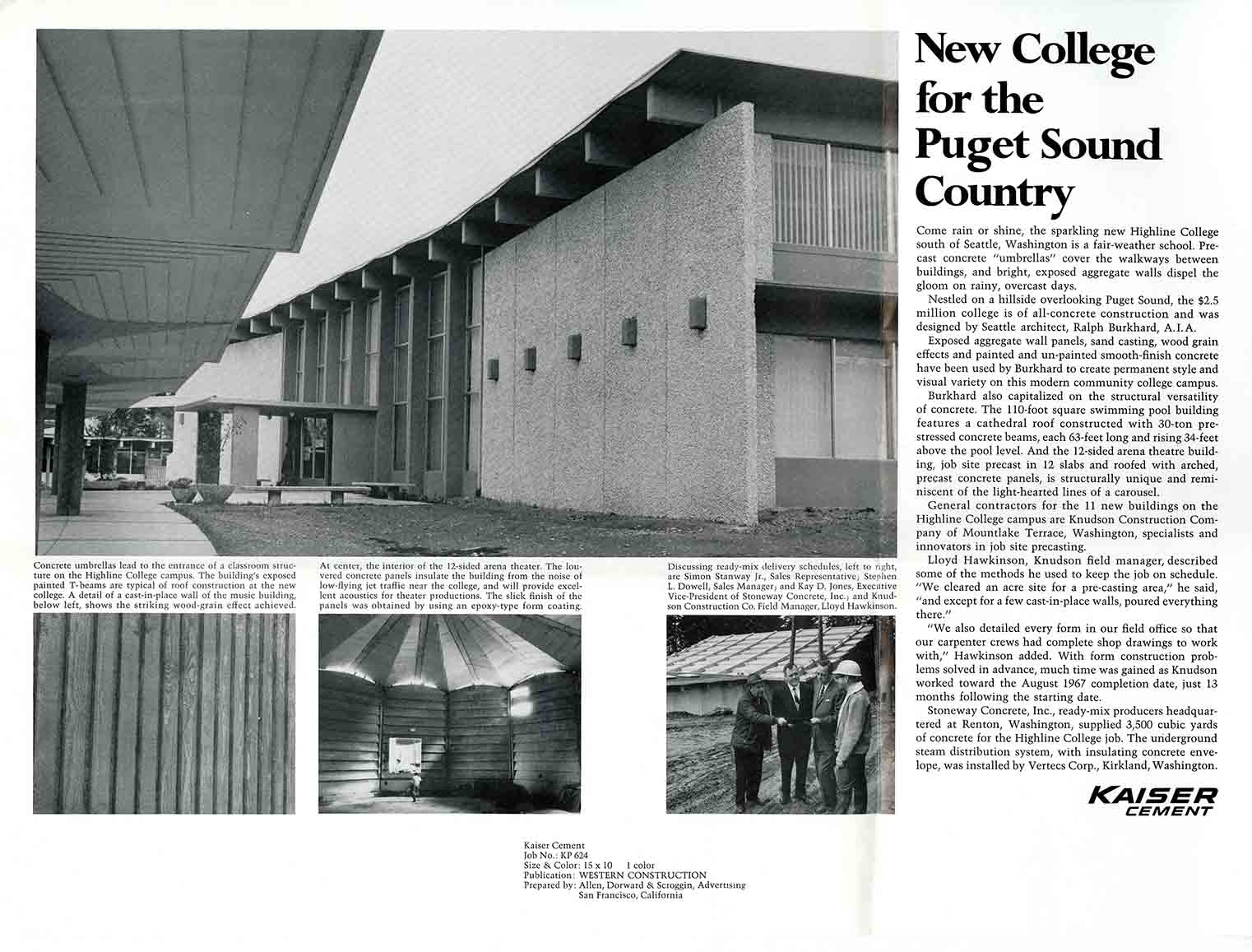

Burkhard’s design called for two, or perhaps three, phases of construction and a liberal use of concrete. In the first phase, campus buildings were clustered along a curving walkway that was protected by a line of concrete “umbrellas.” The buildings themselves were steel-reinforced concrete, either precast or cast in place, with Chewelah marble aggregate coating the exterior walls to make them “attractive, economically maintained, and highly fire-resistant.” [6] The overall effect was bright, crisp, streamlined and modern.

This first phase of construction, involving the original 16 campus buildings, [7] was scheduled for completion in fall 1964. A variety of delays, however, including a plumbers and pipefitters strike as well as the court test of the state’s authority to sell education bonds, had slowed progress, and the 1964–65 academic year opened on a new campus that was still incomplete. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer quipped: “‘Jam Session’ Starts at Highline: New College Offers Instruction AND Construction to 1,500 Students.” [8] The student newspaper, the Thunder-Word, took an optimistic tone: “Buildings Near Their Completion” noted one front-page headline in the October 1964 issue, referring specifically to the Student Center (which has since been replaced by the current Building 8), the library (now Building 6) and the Lecture Hall (today’s Building 7). [9] Landscaping was still unfinished, and for about a year after the campus was occupied, the site had drainage problems. Highline School District superintendent Carl Jensen recalled that “it was necessary to stay on certain walkways or sink into soft mud.” [10]The campus dedication took place on Sunday, January 31, 1965, and was attended by more than 2,800 people, including Governor Dan Evans. The Highline College Faculty Wives Club served tea in the dining area of the Student Center, while faculty and staff members hosted visitors in a campuswide open house. [11]

Students line up to register for classes on the new campus, October 1964. [Click on image to enlarge.]

Students were indeed enjoying the campus. The problem was that there were too many of them either already on campus or trying to get into the college. The first phase of building had been intended to accommodate about 1,000 students, but when classes commenced on the new campus in September 1964, nearly 3,200 were enrolled either part time or full time, and 1,000 qualified applicants had been refused admission. Fortunately, the second phase of construction was already in the planning stages. [13]

Phase II: 1966-67

From the outset, architect Ralph Burkhard had envisioned for Highline a campus that comprised more than thirty buildings. Also from the outset, the new campus was overcrowded. It is not surprising, therefore, that construction of the second phase of buildings got under way almost immediately after the first phase had been dedicated.

This round of construction was slated to include two classroom buildings (today’s Buildings 17 and 22), two vocational and technical buildings (Building 16, which was originally two separate structures), a Performing Arts Center (Building 4), a Data Center/classroom building (Building 21), an Instructional Guidance Center (Building 9), three faculty office buildings (15, 18 and 20 — the last of which has since been torn down), a field for physical education, two new parking lots, and other improvements. A swimming pool would be built as part of this phase of construction but funded separately through student fees. [14]The first step toward making this list of projects a reality, creating a workable design, had been taken when Ralph Burkhard had drawn up the original plans for the campus. Naturally, there would be some changes along the way, but the basic design would remain the same.

Next came gaining the required approval of the Highline School District, since the community college operated under its auspices. In mid-1965, as the process got under way, the anticipated cost of the second phase was about $1.4 million, with between $300,000 and $400,000 of that total to come from bond sales that would need authorization by voters. There was also a possibility that federal funds could be secured. By August 1965, the district had endorsed the plan and begun to move forward on financing. [15]

Third, of course, was actually securing funding for the project. Big news arrived in May 1966, when word came from Washington, D.C., that a federal grant of $1,031,000 had been awarded to the Highline Public Schools for construction at the college. [16] State matching funds added nearly $1 million more, but the money would not go as far as expected, because costs quickly soared.By June, when the school board approved the total costs for construction, electrical and mechanical work, and taxes and fees (including $150,000 for the architect), the sum was nearly double the original estimate. Instead of $1,438,000, the tab would be $2,765,704.83. Among the contributors to the unexpected price increase was a nearly 50 percent rise in the cost per square foot of building space, from an anticipated $17 to $25. In an attempt to keep costs down somewhat, the board scratched plans for a north parking lot, tennis courts and modifications to the science building. [17] But costs would go still higher.

Construction began in summer 1966 and proceeded quickly. When classes started in fall 1967, all of the buildings were completed and in use except for the Instructional Guidance Center, which opened in October, and the Performing Arts Center, finished that December. The new construction added 103,000 square feet of building space to the existing 145,000 and more than doubled the number of classrooms and faculty offices. [18] The final price tag for this phase was $3,775,076. [19]

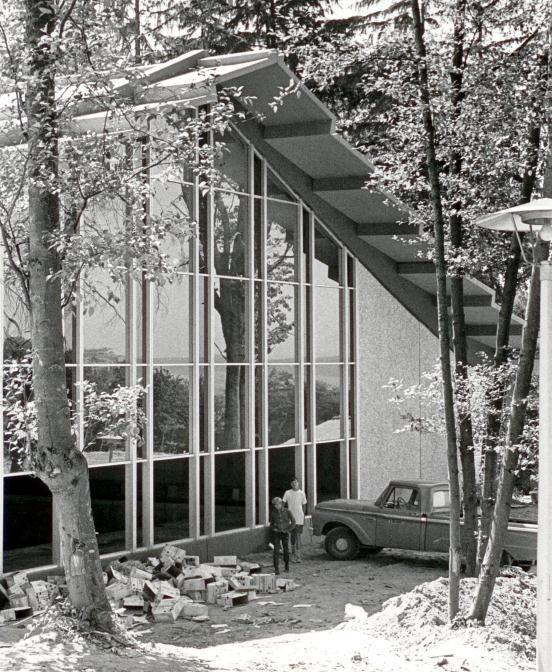

To many observers, the most noteworthy new additions to the campus were the swimming pool and the Performing Arts Center. A Kent News-Journal article titled “Highline College Makes Some Additions to Jet Age Campus” used half of its column inches and three of its five photos to portray those two structures and their associated programs. [20]Once again, concrete predominated. The Kaiser Cement Company, pleased with the results and wanting to promote its own products, took out a two-page advertisement in the trade journal Western Construction featuring the college. “Come rain or shine,” the ad raved, “the sparkling new Highline College south of Seattle, Washington, is a fair-weather school. … Bright, exposed aggregate walls dispel the gloom on rainy, overcast days.” The piece continued: “Exposed aggregate wall panels, sand casting, wood grain effects, and painted and unpainted smooth-finish concrete have been used … to create permanent style and visual variety on this modern community college campus.” [21]

The college advertised the campus additions in its own way, first with an appreciation dinner on Friday, February 9, 1968, for state political leaders, local and state educational figures, and members of the press, then with an open house on Sunday, February 11. According to the Thunder-Word, some 4,000 people visited the campus that weekend. [22]

The second phase of construction had enlarged the campus physical plant significantly, and even more students flocked to Highline. Growth of the student population would continue into the next decade, creating a need for one more major phase of construction.

Phase III: 1974-78

As early as 1970, plans were in the works for a new round of construction, this one not part of Burkhard’s original plan. In fact, this time the college turned to a different architect, Robert Billsbrough Price of Tacoma. Like Burkhard, Price was an award-winning architect of the mid-century modern school with experience designing educational buildings. His original vision, developed with the input of more than two dozen campus committees, was of six connected buildings that would form a U-shaped cluster around a plaza situated down the slope west of the Student Center. This complex would serve as the main instructional center for the campus. [23]

In spring 1970, Highline asked the state for $9.4 million for capital projects, $4.1 million of which would be for the proposed new addition. Other projects would include a $1.3 million expansion of the library. [24] But this was not an auspicious time to request construction funds. The college was not awarded any money for new projects in the 1971–73 biennium. [25] Nevertheless, planning — or perhaps dreaming — continued.

By April 1971, college trustees were considering four different master plans for future construction. None of the plans had funding, but ongoing growth in the student population meant that the need for new facilities remained pressing. The plans anticipated a 100 percent increase in enrollment between 1969 and 1976, with a corresponding doubling of instructional space, from about 250,000 square feet to around 500,000. The preferred plan focused on adding Robert Billsbrough Price’s proposed six-building complex to the upper campus and retaining the lower, western part of the campus for athletic fields and woodlands. It also anticipated the construction of a multilevel parking facility, an idea that has arisen repeatedly over the years without coming to fruition. [26]

Modifying its request for the 1973–75 biennium, the college sketched out plans in spring 1972 for a $10 million “vocational complex.” In addition to providing four buildings for the expansion of vocational programs in Health Occupations, Transportation and Travel, Business and Office Occupations, and more, the proposed complex would also include a new library. [27] That fall, Washington voters approved a referendum calling for a $50 million expenditure on community college construction across the state. Highline had requested $5 million of that total, but the State Board for Community College Education had cut that request down to $2.2 million. By May 1973, even that grant was eliminated, leaving only $3.8 million from other state funds to meet the expected need for new buildings. [28]

Undaunted, Highline proceeded with a two-building project that commenced construction in summer 1974, with an expected final cost of just over $3.7 million. Erected just west of the student union building, these new buildings (today’s numbers 23 and 26) were specifically intended to serve occupational and vocational programs. Finally, Highline would have some room to expand its programs, and college president Orville Carnahan vented his frustration a bit at the delay: “Completion of this addition will come none too soon,” the Thunderword quoted him as saying, “because many of our occupational and vocational programs have been severely cramped. … Educational facilities have to be planned for the long term. Transitory factors such as the ‘energy crisis’ should not deter efforts to provide adequate facilities for the next decade of men and women seeking career training and retraining.” [29]

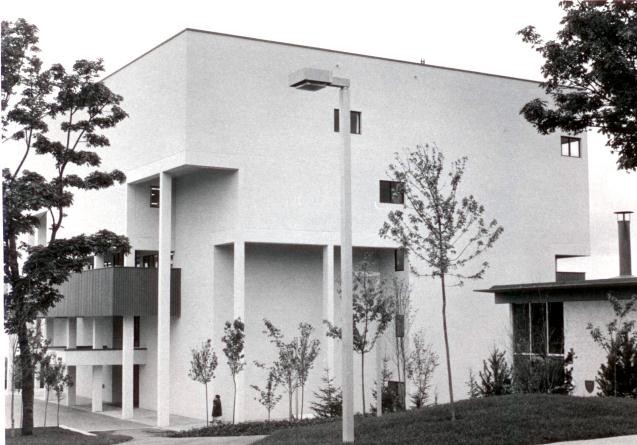

Finished in October 1975, Building 23 originally housed a preschool and programs in Law Enforcement, Home Economics, Fashion Design, Transportation, and Hotel Management. The following month, Building 26 opened its doors to students in the Dental Technician, Nursing, Business Occupations, and Automotive Repair programs. [30]Building of the final element of the third phase of construction, the long-anticipated new library, commenced in fall 1976. Designed by Robert Billsbrough Price, the six-floor structure would seat nine hundred people, three times the capacity of the original library, today’s Building 6. The $3.4 million price tag included not only the library building itself, but also a new softball field, asphalt access roads, and a chilled water plant to provide cooling to the building. [31]

Like its campus predecessors, the library was designed as a contemporary building and was intended to complement other structures, particularly nearby Buildings 23 and 26. Because jets flying into SeaTac Airport had become larger and louder in the years since the campus was first constructed, the library was thoroughly soundproofed. And because the nation had experienced the energy crisis of the early 1970s, the design followed government recommendations for energy efficiency. The result was a large, boxy structure with huge expanses of blank exterior walls and few windows — in the best spot on campus for views of Puget Sound and the Olympic Mountains. [32] Perhaps implicitly acknowledging the design’s limitations, Price observed: “This will be a most functional building.” [33]

Completion of the library was delayed by several problems: severe weather, a carpenters strike, and changes in building plans, according to the contractor; insufficient numbers of workers and water leakage caused by an incomplete roof, according the Highline’s business manager. Rather than opening on January 1, 1978, as originally planned, therefore, the library opened its doors — as campus Building 25 — over spring break 1978. At the time, it was the largest community college building in the state. [34]Acting president Shirley Gordon envisioned the library as the heart of not only the campus, but the community as well. “The library will complete our plaza area . . . and will serve as a hub of the campus,” she said. “One of the important aspects of the new building,” Gordon continued, “is that it will be able to accommodate the community as well as students. We want members of the surrounding communities to be able to come to our library when they wish.” [35] As part of that vision, the library hosted an art museum and gallery for several years beginning in 1979, and it continues to provide space for rotating art exhibits. [36]

As had been the case with the first set of buildings, these three structures received notice by the professional architects of the region. In December 1979, the buildings were given the Award of Merit by the Southwest Washington Chapter of the American Institute of Architects. The award jury commented that the buildings were “interestingly arranged about a paved courtyard” and that they maintained “an agreeable scale despite relatively windowless facades through a sensitive interplay of structure and balcony elements.” [37]

The completion of the new three-building complex marked the end of the third phase of construction on Highline’s campus and rounded out Ralph Burkhard’s original vision of a 30-building plant. Additional campus buildings have become necessary over the years — a new computer lab (Building 30), a replacement for the original student center (Building 8), and a shared Highline/Central Washington University Education Center (Building 29), for example — and remodeling projects are ongoing, but the campus was essentially completed by early 1978.

As the buildings Ralph Burkhard designed approach their own 50th birthdays, it seems appropriate to let the architect have an ironic, posthumous word. Speaking at a conference titled “Problems of School Architecture” at Washington State University in July 1959, he contended “There’s real danger in thinking a school [building] has to last 50 years. I know none that has weathered the educational evolution.” [38] Well, Mr. Burkhard, your buildings and those designed by Robert B. Price have weathered a lot of educational evolutions — not to mention weather itself — over the past several decades. And those same award-winning campus buildings provide the settings for many of the best memories of Highline’s students, faculty, and staff.

About the Author

Tim McMannon teaches American history survey courses, Pacific Northwest history, and the Civil War at Highline College. He earned degrees from the College of Southern Idaho (A.A., 1982), Pepperdine University (B.A., 1985, and M.A., 1987), and the University of Washington (Ph.D., 1994). Before joining the faculty at Highline in 2000, he worked as an adjunct faculty member at several community colleges in the Seattle area and as a researcher in the history of education and teacher education at the Institute for Educational Inquiry.

Notes

1. Until 1967, community colleges in Washington were under the control of local school districts. For its first six years, therefore, Highline College was supervised by the Highline School District Board and Superintendent Carl Jensen.

2. Carl Jensen, “Highline School District Chronicle: The First 100 Years” (no date, c. 1993), pp. 71–72; and “Highline College Plans Approved: $2,342,200 Plant to Serve State,” Renton Record-Chronicle, 22 Aug. 1962, p. 12. Newspaper articles cited in this document (other than those from the student newspaper, the Thunderword) are from the clipping collection of the Institutional Advancement Office; in some cases, exact dates and/or page numbers are unavailable.

3. Jensen, Highline School District Chronicle, p. 71; and “New Highline College to Open,” Seattle Times, 30 Aug. 1964.

4. Reid Hale, “Construction of Highline College Delayed: Court Test of State School Bonds Stalls Work on New Campus As Long As One Year,” Highline Times, 27 June 1963; and “Junior College: Highline Groundbreaking Set,” Seattle Times, 11 Aug. 1963.

5. See “Ralph Halbert Burkhard” in the Pacific Coast Architecture Database and Burkhard, Ralph H., at docomomo WEWA (Documentation and Conservation of the Modern Movement, Western Washington).

6. “Most Up-to-Date Concepts Available Go into Planning and Construction of Campus” in “Highline College Dedication Issue” (supplement, Highline Times and Des Moines News Advertiser), 27 Jan. 1965, p. 14.

7. The original buildings were today’s numbers 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 19, 24, 27, and 28.

8. 29 Sept. 1964, p. 6.

9. The newspaper name has evolved over the years from Thunder Word to Thunder-Word to Thunderword. I have tried to use whatever name was then current. Back issues, including all those cited in these notes, are available at the Thunderword Archive.

10. Jensen, “Highline School District Chronicle,” p. 72.

11. “Highline College: 2,800 at Campus Dedication,” Seattle Times, Feb. 1, 1965, p. 6; and “Dedication of Highline College,” brochure, 31 Jan. 1965.

12. “Highline College Wins Design Award,” Seattle Times, 5 Feb. 1966; “Local Architect Ralph Burkhard Receives National Award for Highline College Design,” Highline Times, 9 Feb. 1966; and “Highline and Burkhard Win National Citation,” Highline Thunder-Word, 25 Feb. 1966, p. 1.13. “New Highline College to Open,” Seattle Times, 30 Aug. 1964; ‘Highline Enrolls 3,184 for Fall Classes,” Kent News Journal, 14 Oct. 1964; Maribeth Bunker, “Post-War Babies out in Cold at Colleges,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 11 Aug. 1964, p. 1; and “The Story of the College” in “Dedication of Highline College,” brochure.

14. “Highline Gets Go-Ahead for 2nd Addition,” Des Moines News, 18 Aug. 1965, p. 12.

15. “Highline Gets Go-Ahead for 2nd Addition.”

16. “Highline JC Receives $1,031,000 Fed. Grant,” Highline Times, 25 May 1966.

17. “Highline College Construction $2,765,704: Bid on 2nd Phase up $8 Per Sq. Ft.,” Highline Times, 15 June 1966, pp. 1, 3.

18. “Highline Community College Gains Eleven New Buildings,” Thunder-Word, 29 Sept. 1967, pp. 1, 4; and “Performing Arts Center Opens,” Thunder-Word, 8 Dec. 1967, p. 6.

19. “Thousands Visit Campus Dedication,” Thunder-Word, 16 Feb. 1968, p. 1.

20. “Highline College Makes Some Additions to a Jet Age Campus,” Kent News-Journal, n.d. [Feb. 1968].

21. Allen, Dorward & Scroggin, Advertising, “New College for the Puget Sound Country,” advertisement in Western Construction (volume and date unknown).

22. “Thousands Visit Campus Dedication,” Thunder-Word, 16 Feb. 1968, p. 1.

23. “HCC Planing [sic] for Expansion,” Thunder-Word, 30 Jan. 1970, p. 1; and “Highline Community College Seeking State Funding for $9 Million in Capital Projects,” Kent News-Journal, 6 May 1970, p. 26.

24. “Highline Community College Seeking State Funding,” p. 26; and “Highline CC Expansion,” Highline Times, 6 May 1970, pp. 1+.

25. “Highline College Trustees Evaluate Master Plan Possibilities for ’70s,” Federal Way News, 21 Apr. 1971.

26. “Highline College Trustees”; and “Master Building Plan Presented to Trustees,” Thunder Word, 23 Apr. 1971, p. 1.

27. Dineen Gruver, “HCC Plans Ahead: $10 Million Complex Sought for 1976,” Thunder-Word, 19 May 1972, p. 24.

28. Dineen Gruver, “Voters Authorize $50 Million for CCs; Question … When … And How Much?” Thunder Word, 8 Dec. 1972, p. 1; and Dineen Gruver, “State Cuts Building Fund,” Thunder Word, 18 May 1973, p. 4.

29. “Construction to Begin on Two New Buildings,” Thunder Word, 1 Feb. 1974, p. 2.

30. “Highline on the Move,” Thunder Word, 22 Sept. 1975, p. 1.

31. “Library Contract Awarded to Absher,” Thunderword, 27 Sept. 1976, p. 1; “New Six-level Library in 1978,” Thunderword, 27 Sept. 1976, p. 1; and “It’s on the Books: Library to Complete Campus Trilogy,” Des Moines News, 26 Sept 1976.

32. “New Six-level Library”; and “It’s on the Books.”

33. “It’s on the Books.”

34. “Work Stoppage Now Over,” Kent News Journal, 3 Aug. 1977; John Miller, “$15,000 New Library Refund: Penalty Clause May Be Called,” Thunderword, 24 Feb. 1978, p. 1; and John Miller, “After Many Delays: Library Finally Finds a New Home,” Thunderword, 7 Apr. 1978, p. 12.

35. “It’s on the Books.”

36. “Library’s Extra Space Will be Turned into a Gallery-Museum,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 28 Feb. 1979.

37. Carl Lizberg, “Five Projects Cited by AIA,” Tacoma News Tribune, 30 Dec. 1979; and “5 Projects in South Sound Area Honored by Architects’ Group,” Seattle Times, 30 Dec. 1979.

38. “Problems of School Architecture,” Proceedings of the A.A. Cleveland Conference, Washington State University, 20–21 July 1959, p. 1. Document accessible from the Historic School Preservation page through Washington State’s Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation.