1968: Protest Comes to Highline

By Dr. Tim McMannon

Read McMannon’s other vignettes, “Highline College: Why Here? Why Then?” and “Our Award-Winning Campus (Buildings!),” both published electronically in conjunction with the college’s 55th anniversary celebration during the 2016–17 academic year.

Highline College prides itself on its appreciation of diversity, and rightly so: the college has the most diverse student body of any two-year school in Washington and has worked hard to build an increasingly diverse faculty and staff.

The college annually observes Martin Luther King Jr. Week, Unity Through Diversity Week, LGBT Awareness Month, Asian Pacific Islander Month and more, marking those occasions with lectures, discussions and other activities. And students earning an Associate of Arts degree are required to take at least one course that qualifies as Diversity and Global Studies.

But the school has not gone entirely without confrontations and difficulties. Occasionally, we hear about the destruction of a group’s signs, the appearance of racist graffiti or other indications of intolerance. And occasionally a group will make a public stand when its members feel that they are not being treated appropriately. Two memorable confrontations took place at Highline in 1968, both involving African-American students and both ultimately helping to shape the development of Highline’s institution-wide respect for diversity.

Historians of post–World War II America would not be at all surprised that 1968 was a year of unrest at Highline. It was certainly a year of crisis for the United States. Every month seemed to bring the country some new surprise, disappointment, horror or protest, and college campuses were frequently the scenes of turmoil.

On January 23, the United States was embarrassed and angered by North Korea’s seizing of the spy ship USS Pueblo. Just one week later, the Tet Offensive, carried out by North Vietnamese forces against South Vietnamese and American installations in the south, seemed to prove that the United States could not win in Vietnam and that the nation’s political and military leaders had intentionally misled us about our prospects there.

At the end of March, weighed down by the difficulties of the war as well as domestic problems, President Lyndon Johnson withdrew from the presidential campaign. A few days later, on April 4, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, and America’s cities erupted in violence. With the nation still reeling from King’s murder, Robert Kennedy was assassinated in early June, having just won the California presidential primary to become the Democratic frontrunner.

August brought not only the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia but also the Democratic convention in Chicago, known for police violence against protesters. By the end of the year, Richard Nixon had been elected president, promising law and order in the United States and peace with honor in Vietnam. Neither promise would be fulfilled quickly or completely.

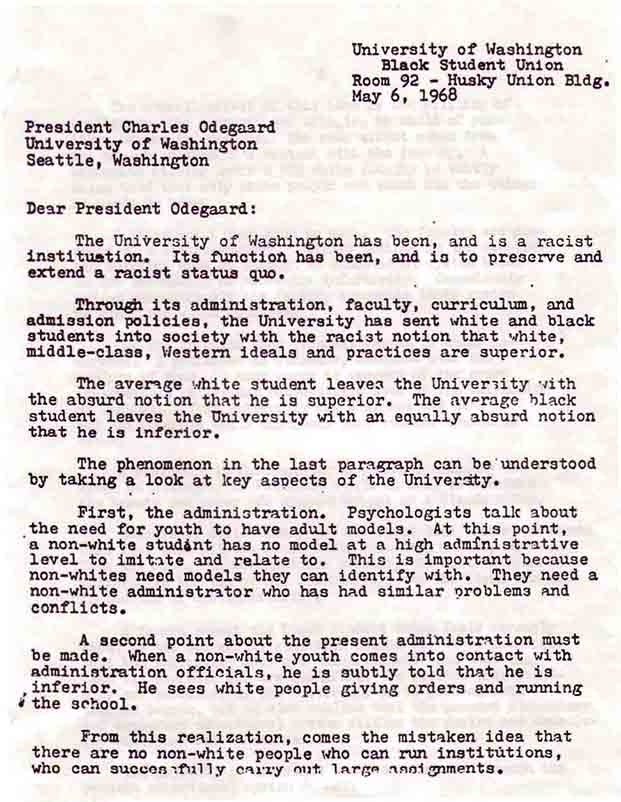

The first of a four-page letter sent 5/6/1968 to UW President Odegaard from the newly formed Black Student Union calls the institution “racist.” Credit: University of Washington. [Click on image to enlarge.]

The first moves were made at the University of Washington. The newly formed Black Student Union (BSU) helped to establish similar organizations at local high schools and middle schools, participated in a sit-in at Franklin High School (resulting in the arrest and incarceration of several BSU leaders), and founded the Seattle chapter of the Black Panther Party. [1]

On May 6, 1968, the BSU sent UW president Charles Odegaard a letter describing the UW as a “racist institution,” outlining a number of grievances, and making five demands:

- All decisions, plans, and programs affecting the lives of black students must be made in consultation with the Black Student Union. …

- The Black Student Union should be given the financial resources and aids necessary to recruit and tutor non-white students. …

- We demand that a Black Studies Planning Committee be set up under the direction and control of the Black Student Union … to develop a Black Studies Curriculum that objectively studies the culture and life-style of non-white Americans. …

- We want to work closely with the administration and faculty to recruit black teachers and administrators.

- We want black representatives on the music faculty.[2]

By Thursday, May 9, Odegaard had responded, indicating his willingness to work with the BSU to establish a “mechanism for consultation” that would allow the organization to give advice as the university moved forward. [3] The first step in creating that mechanism was a meeting held on Monday, May 13, between Odegaard and the BSU. Although that meeting was initially described as “encouraging,” by the end of that week, the BSU was demanding $50,000 to fund the Black Studies Program. When the money was not forthcoming, BSU members and supporters staged a sit-in at the Administration Building. [4]

In the meantime, students at Highline were following the lead of the UW’s BSU. On Monday, May 13, the same day as the meeting between Odegaard and the BSU, members of Highline’s Afro-American Society, a student group so new to the college that it had not yet been formally recognized as a campus organization, gave college president Melvin A. “Pat” Allan a list of five demands — and a five-day deadline for his response. These demands were precisely the same as those submitted to Odegaard, with the substitution of “Afro-American Society” for BSU. [5]

Although Allan, like Odegaard, must have been a bit miffed by the ultimatum and its attendant deadline, he nevertheless responded in respectful but firm tones on May 17, just four days later. In his reply, he assured the Afro-American Society that he valued its input as he did the “comments, suggestions, and recommendations of all registered students.”

“Your help in the solution of the problems you identify,” he continued, “can be of great value to you, your fellow students of all races, and to this community college.” Allan also asked the instructional deans and division chairs to meet with “representatives of the Afro-American Society and with other student groups [that] request to be heard” to develop curriculum focused on “the history, culture, lifestyle, and needs of non-white Americans.” Finally, he reminded the students that some things were not negotiable:

It should be made clear, however, that certain areas of decision are assigned by law to the Trustees and to the President. These cannot be delegated. Certain other areas are by law or regulation reserved to the faculty and the recognized student government of the College. These authorities will be maintained. [6]

In short, he was willing to allow the Afro-American Society to have input, in common with other students and student groups, but he was not willing to turn over the keys to the college.

On May 21, President Allan and Reid Hale, chairman of Highline’s Board of Trustees, met with representatives of the Afro-American Society. In the words of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, they reached “agreement on several areas of future action regarding a black-studies program and recruitment of Negro teachers and administrators.” [7]

Dialogue between Highline administrators and the Afro-American Society would continue, and as the academic year came to an end that June, it appeared that the school had managed to avoid the kinds of conflict that had arisen at Franklin High School, the UW, and some of the other area colleges. But the following fall quarter was not even a month old before an incident would occur to shatter the peace.

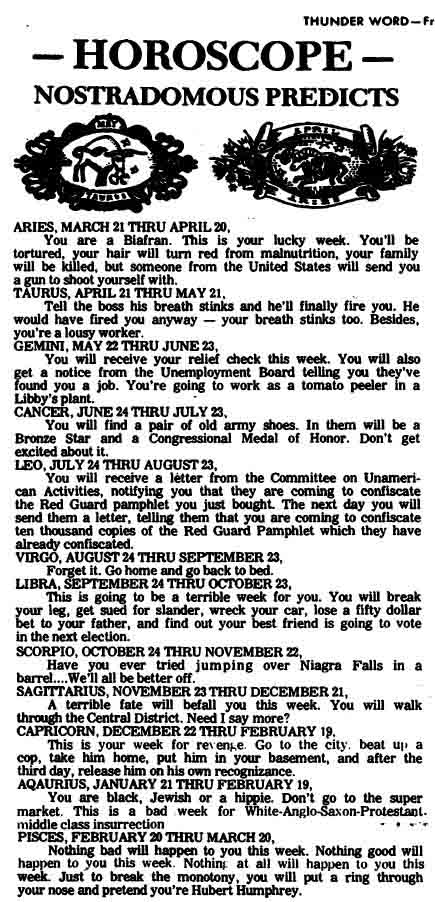

The October 18, 1968, issue of the Thunder Word (the newspaper title was still treated as two words then) included a horoscope section that was intended to be satirical. For example, the entry for Taurus read: “Tell the boss his breath stinks and he’ll finally fire you. He would have fired you anyway — your breath stinks too. Besides, you’re a lousy worker.” Several of the items, however, could easily have given offense. Aquarius read: “You are black, Jewish or a hippie. Don’t go to the super market. This is a bad week for White-Anglo-Saxon-Protestant- middle class insurrection.”But the item that sparked the greatest reaction was the “horoscope” for Sagittarius. “A terrible fate will befall you this week,” it predicted. “You will walk through the Central District. Need I say more?” [8]

The author, Thunder Word editor John Nelson, did not need to say more. The Central District was Seattle’s main black neighborhood. The insult was clear to Highline’s African-American students, many of whom lived in the Central District, and they were not about to let it go unchallenged.

The first step taken by the renamed Afro-American Union (or AAU, still called the Afro-American Society in some sources) was to ask Nelson for a retraction and a public apology. [9] AAU president Harrison Allen III and AAU officer Steve Tolliver met with him three times, but Nelson refused to issue an apology, saying that incidents that had happened either to him or to his friends justified his characterization of the Central District.

The next step was to hold a forum on campus at which the Afro-American Union explained the reasons for the organization’s strong reaction against the statement. When Nelson spoke at the forum, he vowed that he would not apologize, and the audience, mostly white students, applauded. Harrison Allen later observed:

The Afro-American Union recognized the seriousness of the situation. Either Mr. Nelson was deliberately using the influence of his office to impair the black and white student relationship or, if he were acting without willful malice, his conduct exposed him [as] a barrier to racial amity on campus and in community relations. Clearly, then, the interests of racial amity required that Mr. Nelson be relieved of the office of editor. [10]

The AAU pursued Nelson’s dismissal, but neither the paper’s faculty adviser Betty Strehlau nor Dean of Students Jesse Caskey nor President Allan would take that step. Feeling that they had exhausted all options available to them through normal channels, AAU members decided to resort to the strategy that had been used at Franklin High School, the University of Washington, and at lunch counters across the South: a sit-in.

On October 31, 20 to 30 (accounts vary) black students led by Afro-American Union officers entered the newspaper office, which also served as the journalism classroom. [11] Editor John Nelson was working in the room and was told to resign his position or leave the room within one minute. He left the room. He then informed Dean Caskey what had happened. Meanwhile, the students who were staging the sit-in barricaded the room with desks and chairs.

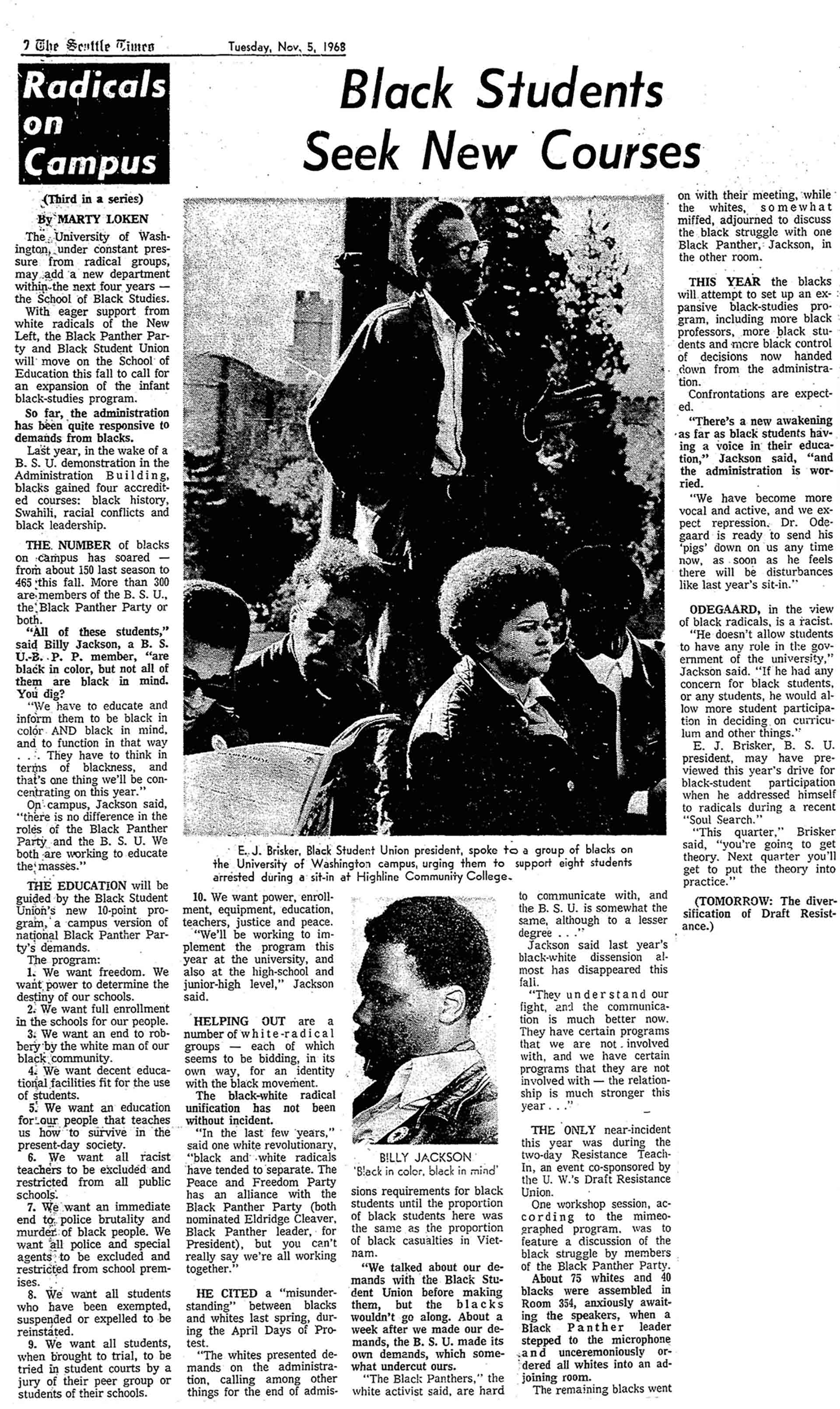

The photo caption of the 11/5/1968 Seattle Times article reads, “E.J. Brisker, Black Student Union president, spoke to a group of blacks on the University of Washington campus, urging them to support eight students arrested during a sit-in at Highline Community College.” Credit: Seattle Times archive. [Click on image to enlarge.]

While they were awaiting trial, John Nelson had at least a partial change of heart, perhaps encouraged by the administration. On the front page of the November 15 issue of the Thunder Word appeared an open letter of apology, cosigned by Nelson and Allan. The letter read, in part: “We regret that this offense was given and that personal feeling or the dignity of any district were injured. It was not the intent of the author of this column to do such injury.” [12]

Nelson continued his mea culpa in his “Rantings & Ravings” column in the same issue: “My first error was in printing the statement and the second was my lack of sympathy with the position taken by the many responsible students on campus who opposed my stand. I hope now that the situation can be remedied, and although errors in judgment have been made on both sides, I feel it is my duty to act first. I can only add that my actions should have come sooner, avoiding all the problems which have arisen.” [13]

His references to “responsible students” — implying that there were also irresponsible ones who opposed him — and “errors in judgment … on both sides” imply that he did not necessarily see his own actions as being the most troublesome. And by claiming to act first, he seemed to indicate that he thought that he was taking the moral high ground and that others owed him an apology. Perhaps so; he must certainly have been frightened when a couple dozen students confronted him at the Thunder Word office and told him to resign or get out.

In the meantime, the Highline Board of Trustees held its November meeting. The board commended the administration for eight specific actions in dealing with incidents surrounding the sit-in, including:

- Authorization and establishment of the Afro-American Society as a student organization to speak for its minority group members and those who associate themselves with it and with its operations.

- Vigorous efforts to recruit non-white students from high schools in the area.

- Curricular adjustments and modifications to meet the needs of black students, and the continuing study of such adjustments for minority students. …

- Vigorous and successful effort to expand financial aids to black students.

- Public censure of the editor of the student newspaper for his inappropriate action and prompt apology to persons who may have been injured by the editorial content of the paper. …

- Acting toward the establishment of a Central Area Citizens Advisory Committee to the President.

- [14]

According to the White Center News, the board was careful to note that the actions had been taken “during the past several months [emphasis added] in planning for adjustments needed, and in meeting disturbances associated with, the concerns of minority group students and citizens.” [15] In other words, readers were to assume that changes were already underway at Highline even before the sit-in. One cannot help but wonder, however, if all of these steps would have been taken without it.

And what of the students who carried out the sit-in? After a brief delay in the trial, as well as the separation of the trial of one student from that of the other seven, they were found guilty. They were given deferred sentences: charges would be dismissed after six months, provided that they did not commit any crimes during that time. [16] There is no evidence to indicate that any of the students had further run-ins with the law. Through the use of peaceful civil disobedience, they had made their point and helped to bring about change, change that is still part of the culture at Highline College.

About the Author

Tim McMannon teaches American history survey courses, Pacific Northwest history, and the Civil War at Highline College. He earned degrees from the College of Southern Idaho (A.A., 1982), Pepperdine University (B.A., 1985, and M.A., 1987), and the University of Washington (Ph.D., 1994). Before joining the faculty at Highline in 2000, he worked as an adjunct faculty member at several community colleges in the Seattle area and as a researcher in the history of education and teacher education at the Institute for Educational Inquiry.

Notes

1. Marc Robinson, “The Early History of the UW Black Student Union.”

2. Black Student Union to President Charles Odegaard, 6 May 1968.

3. See Fred Olson, “Odegaard Gives Answers to BSU Demands,” University of Washington Daily, 10 May 1968, pp. 1, 3; and “Full Text of Odegaard’s Reply to BSU” pp. 1–2. The opening paragraphs of these articles may be found on “Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project,” University of Washington, accessed 9 August 2018.

4. Robert Cour, “UW Negroes Air Demand for $50,000,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 18 May 1968. The opening paragraphs of this article may be found on “Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project,” University of Washington, accessed 9 August 2018; and Robert Cour and Fergus Hoffman, “4-Hour Negro Sit-in at UW; New Talks Set,” (page 1), Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 21 May 1968, with article continuing on page 8 (“Four-Hour Negro Sit-in”).

5. See Jim Shahan, “Highline Afro-American Society Makes 5 Point Demand,” Federal Way News, 22 May 1968; “Text of Dr. Allan’s Reply,” Federal Way News, 22 May 1968; “Afro-American Highline Group Tells 5 Demands,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 21 May 1968; John DeYounge, “Black Student Demands Met at Highline,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 22 May 1968; and “Dr. Allan Answers ‘5 Demands,’” Thunder Word, 5 June 1968, p. 1.

6. All quotations from “Text of Dr. Allan’s Reply.”

7. John De Younge, “Black Student Demands Met at Highline,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 22 May 1968.

8. “Horoscope: Nostradomous [sic] Predicts,” Thunder Word, 18 October 1968, p. 3.

9. The following account comes from an article written by Harrison Allen III, “Sit-in Incident: Highline Black Students Express Thier [sic] Views,” published in The Facts, a Central District newspaper, in November 1968. As a result, it is naturally somewhat biased in favor of the Afro-American Union, but it does seem to align with information available from other sources. There does not seem to be a similar summary by John Nelson.

President Allan described the incident in his memoirs, but his account varies somewhat from other evidence. It is likely that he had knowledge and experiences that were not reflected in the newspapers. For example, he describes a visitor who came from the University of San Francisco and made the following demands:

- One-fifth of the faculty and student body to be black.

- A Black Studies program to be introduced as a required sequence.

- Special tutoring for black students.

- No denial of admission because of race.

- Provision of a special lounge open to black students only.

Although this visitor’s list of demands overlaps with the list in the Afro-American Society’s letter quoted in the Thunder Word and other local newspapers, there are some clear differences. Allan’s account continued:

I said I would respond in writing, through the school newspaper, which I did, allowing that some of the demands were reasonable and proper, while others could and would be implemented only in part, and some were unreasonable or illegal or impossible, and I didn’t intend to waste staff time trying to achieve them.

The student editor published an editorial supporting my views.

Thereupon, the black students, of whom we had a higher number than had the University of Washington, staged a sit-in in the journalism classroom, barricading the door. (From M.A. Pat Allan, “Memoirs,” p. 255.)

10. Harrison Allen III, “Sit-in Incident: Highline Black Students Express Thier [sic] Views,” The Facts, November 1968.

11. In addition to Harrison Allen III’s account, cited in notes 9 and 10 above, see “Eight Highline College Students Arrested Friday,” Highline Times, 6 November 1968.

12. “A New Stand on an Unfortunate Occurrence,” Thunder Word, 15 November 1968, p. 1.

13. John Nelson, “Rantings & Ravings,” Thunder Word, 15 November 1968, p. 2.

14. “Highline College Trustees Commend ‘Minority Crisis’ Action by Allan,” White Center News, 27 November 1968, p. 14.

15. “Highline College Trustees.”

16. “Sit-In Students Sentencing Delayed,” Des Moines News, 11 December 1968.